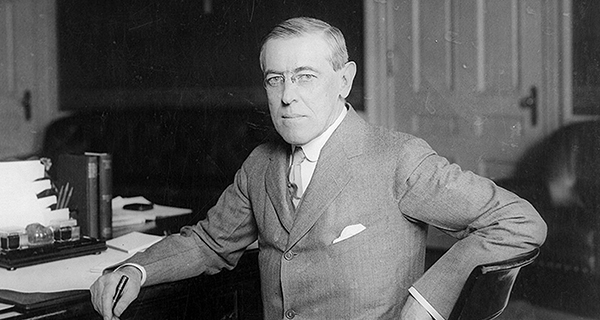

When the Paris Peace Conference opened on Jan. 18, 1919, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson seemed to be at the top of his game.

When the Paris Peace Conference opened on Jan. 18, 1919, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson seemed to be at the top of his game.

America’s entry had played a critical role in ending the First World War and Wilson’s famous Fourteen Points were acclaimed as the blueprint for a just settlement and a future world where democracy, peace and non-aggression would be the order of the day.

It didn’t turn out like that.

Just over 20 years later, an even more destructive war would break out. And less than two years after the conference opened, Wilson would see his diplomatic handiwork irretrievably flounder in the U.S. Senate.

Because of the Senate vote, there would be no American membership in Wilson’s cherished League of Nations. So, broken in health by a severe stroke, his dream was in tatters when he left the White House at the conclusion of his second term in 1921.

Wilson (1856-1924) was born in Virginia and raised in Georgia and South Carolina. An academic by nature – he remains the only PhD ever elected to the presidency – he was an admirer of the British parliamentary system, preferring its centralization of executive power to the checks and balances of the American arrangement.

It’s reasonable to surmise that Wilson’s preference wasn’t just intellectual. It also suited his personality. To quote historian Alvin Felzenberg, “he insisted on having his own way on all things he deemed important.” Compromise just wasn’t his thing.

Elective politics entered Wilson’s life in 1910. He’d been Princeton University’s president since 1902, in the course of which he attracted the attention of New Jersey Democratic power brokers, who saw him as an attractive gubernatorial candidate. He ran and won, and then used the governor’s position as a springboard to the 1912 U.S. presidential race.

After finally securing the Democratic presidential nomination on the 46th ballot, Wilson caught a major break. The rival Republican Party was badly split, so much so that the loser in its nomination battle ran on a third-party ticket in the general election. And with the Republican vote thus spread over two candidates, Wilson became the first Democrat to win the presidency in 20 years.

Wilson was well into his second term when he promulgated his Fourteen Points and went to Paris.

Not everyone was impressed.

To French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, it all smacked of moral posturing. His sarcastic reaction to the Fourteen Points was that “the good Lord only had 10!”

But while the European leaders chipped away at Wilson’s principles in the detailed treaty negotiations, they left his League of Nations concept more or less intact. It was back home that the idea came a cropper.

Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge (1850-1924) was Wilson’s domestic nemesis. They had one thing in common: Lodge, too, was a PhD, in his case a history doctorate from Harvard.

Lodge wasn’t an isolationist. Nor was he inalterably opposed to the idea of a League of Nations. However, he had serious reservations about the way it was structured. Most critically, he didn’t like Article X, which he believed had the potential to ensnare the U.S. in unwanted foreign wars.

Article X required League of Nations members to come to the assistance of any member who was subject to external aggression. If the League of Nations deemed it necessary, military means were to be used.

Lodge was afraid that this would subvert the constitutional authority of Congress, which had the sole power to declare war.

Accordingly, he tabled a number of reservations to be explicitly attached to Senate approval of the treaty. One of these addressed Article X.

Specifically, “The United States assumes no obligation to preserve the territorial integrity or political independence of any other country or to interfere in controversies between nations … unless in any particular case the Congress, which under the Constitution has the sole power to declare war or authorize the employment of the military or naval forces of the United States, shall by act or joint resolution so provide.”

Wilson, though, was having none of it. Insisting that the treaty didn’t negate Congress’s constitutional authority, he refused to incorporate the Lodge reservations. Consequently, the Senate withheld approval and the U.S. never joined the League of Nations.

Imbued with his own rectitude, Wilson had difficulty dealing with the division of powers inherent in the American system. So he left empty handed.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps just a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.